About the Caspian Horse

Introducing the Caspian Horse

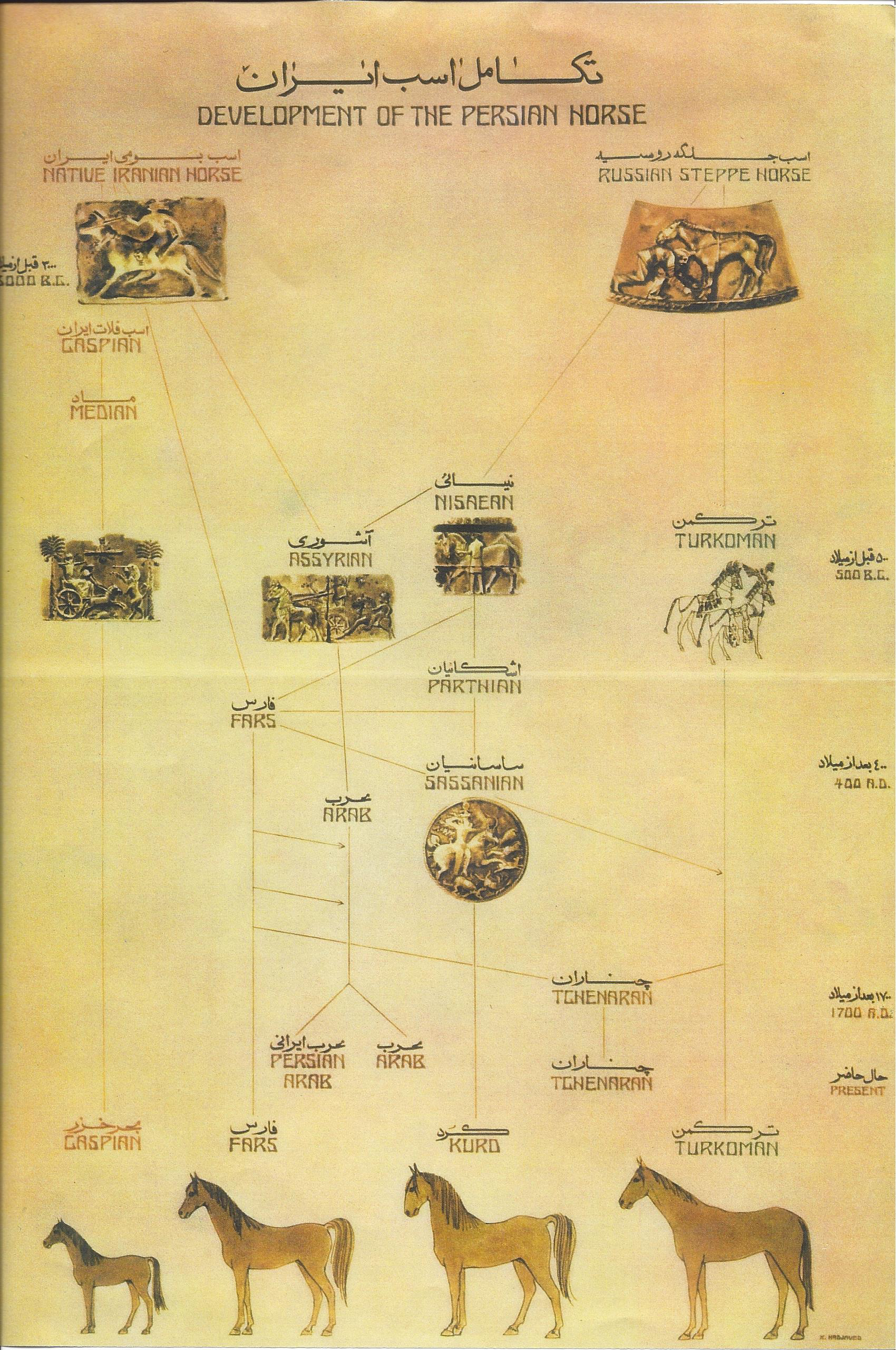

Until 1965 the Caspian horse was virtually unknown outside a small mountainous area of Northern Iran. Research into his origin produced theories which now reverberate throughout the horse world. The Caspian is a horse (although it stands only 9 hands – 12.2 hands) and almost certainly dates back to 3000BC. The breed is important as the possible prototype Arabian. The findings of a project conducted by Kentucky University places Caspian and Turkoman horses in an ancestral position to all breeds researched to date.

Attempts by Louise Firouz, who re-discovered the breed in 1965, to expand the small remnant population in Iran, were repressed by revolution and war. The removal of a small number to the UK, prompted by HRH Prince Philip and the achievements of a small nucleus of individual breeders in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Scandinavia have ensured their existence today.

It is a versatile performer and excels at jumping and in harness, with the quality and action that enable the Caspian to compete successfully in the show ring with any member of the family. The Caspian is an ideal mount for small children, narrower than native breeds, possessing the elegance, intelligence and love of people attributed to the Arab.

History of the Caspian Horse Breed

In 1965 Louise Firouz, the American-born wife of an Iranian aristocrat, chanced upon a sleek, dark bay stallion darting around the streets of a coastal market town in northern Iran. A slender, fine-boned animal with flowing mane and tail, Ostad* pulled a heavily laden cart with dash and flair. This was no ordinary pony. So impressed was his observer that she persuaded the owner of Ostad to sell him to her. At last she had found something suitable for her children to ride. She began to make extensive enquiries about the breed.

Despite worldwide appreciation for exotic Persian cats and carpets, it is understandable that few people have ever heard of the Caspian horse, which it was thought had become extinct. The breed dates back to ancient Persia, at least as far as 3,000 B.C. and, in 500 B.C., it delighted King Darius the Great with its prowess in harness when hunting lions. Darius honoured the Caspian with a place on his royal seal and portrayed him in stone on the staircase of his palace in Persepolis.

The villagers referred to them as “Mouleki” or “Pouseki”. Unlike other Iranian breeds, they were not deliberately bred. They were throwbacks, which then bred true to type and size. Therefore, every now and again, a full-sized mare would give birth to one of these miniatures.

Louise Firouz began a search which was to take several years, over vast areas of inhospitable mountainous terrain, during which she found only a handful of Caspians. Averaging only 11.2 hands high, the Caspian made gentle, willing mounts for small children, yet they had the bearing, spectacular action, build and speed of a highly bred horse. Their jumping ability was little short of spectacular and they showed the speed and agility that had so impressed King Darius so many centuries before. Even the stallions were ridden and raced by children of only five years old. They were turned out together without trauma and ridden in the company of mares in the riding school that Louise and her husband Narcy ran with great success.

In 1966 she exported the stallion Jehan* to her friend Kathleen McCormick in the USA. In 1971, during the Celebration of the Peacock Throne, a mare and stallion were presented to HRH Prince Philip. Two years’ quarantine in Hungary produced a filly en-route to the UK. Two mares and a stallion were taken back to Bermuda by Joan Taplin, a friend who had accompanied her on her hunt for the little horses. Another stallion was exported to Surrey, England, and an in-foal mare and her colt were exported to the Caspian Stud UK in Shropshire. The stud, prefix ‘Hopstone’, later also bought the stock from Bermuda and became the custodians of the horses belonging to HRH Prince Philip.

At this stage the (then) Royal Horse Society in Iran took an interest in the Caspian and bought the remaining herd, but royal patronage ultimately spelled disaster for the breed.

The following year a further shipment was sent to the Caspian Stud UK, some of which were put in foal to UK stallions before continuing their journey to New Zealand and Australia. By 1976, Louise had built up a new herd in Iran, numbering around 24. Living a semi-nomadic existence, she provided food for the herd by shepherding them seasonally between grazing. The following spring two of her finest mares and a young foal were killed by wolves and Louise arranged an emergency shipment of seven mares and a stallion to join the stock already at the Caspian Stud UK.

The former Royal Horse Society of Iran were not impressed by the publicity surrounding the evacuation and confiscated the remaining herd in Iran. Already pitifully reduced by famine, the herd was sold off following the revolution, mostly for meat. Only one stallion, Zeeland, was known to have survived.

Bas-relief from Naqsh-e Rostam, Tomb of Persian Kings, Iran

The Oxus Treasure – British Museum

Bas relief from Naqsh-e Rostam, Tomb of Persian Kings, Iran

Part Bred Caspian – Menagerie Mack the Knife – USA

At this point the breed might well have reverted back into a Persian fairy tale, had it not been for the dedication of a small band of owners in Britain, New Zealand and Australia, led by the Caspian Stud UK, owned by Elizabeth Webster, her mother Stephanie Jenvey and business partner Arthur Griffin. As well as shouldering the tremendous burden of responsibility for the stud, and indeed the survival of the breed, they formed the British Caspian Trust and officially published the International Caspian Stud Book.

As the bulk of the stock had been bred from a minimal nucleus of foundation animals, the immediate danger was that of inbreeding. This they combated by using a system of line and cyclic crossing, devised by Lawrence Alderson (Rare Breeds Survival Trust); mating each foundation mare to a different foundation stallion in turn, compensating as appropriate.

Following the revolution, there was a ban on keeping more than one horse in Iran. The remaining Caspians were turned loose and eventually swept up to assist in the war effort with Iraq. At the end of the war, Louise was invited to visit a large building which housed over 1,000 repatriated animals. Amongst these she found a few Caspian horses, which formed the basis of a new herd in Iran.

In 1994 a shipment of seven Caspians was allowed out of Iran, breathing new blood into the minimal number of bloodlines available throughout the rest of the world.

At around the same time, horse enthusiasts in the USA became interested in the breed and almost all UK and Australian stock under two years of age between 1994 and 1997 were sold to the USA. In 1998 a shipment of Caspians was exported from the UK to Scandinavia and small breeding establishments now exist in Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, Holland, Switzerland, Brussels and Denmark, with interest expressed from Russia and Poland.

After almost 40 years of breeding, the number of live breeding animals outside Iran total no more than 1000 worldwide.

The exquisite little horse has been the subject of a great deal of controversy and research, which established that the bone structure is that of a horse rather than a pony. Experts now believe the Caspian to be the forerunner to the Arab horse and hence to most of the hot blooded horses in existence today.

Small numbers of feral animals are still found and bred in Iran.

Cross-bred with Arabians and Thoroughbreds they maintain all the attributes of the breed, with the extra height that makes them more versatile for the older rider. There have also been crosses made with other breeds such as Dartmoor, New Forest, Welsh and Shetland, which have proved to inherit much of the athleticism and other excellent characteristics of the Caspian.

The Caspian Horse Breed Standard

General:

The Caspian is a breed of small horses with distinctive characteristics that originated from the surviving population in their native territory in northern Iran. It is a horse, not a pony, and therefore should be viewed in the same manner as when judging a well-bred horse, that is, the limbs, body and head should all be in proportion to each other. Foreshortened limbs or a head out of proportion are faults. The overall impression should be that of an elegant, small horse.

Eyes:

Almond shaped, large, dark, set low, often prominent.

Nostrils:

Large, low set, finely chiselled, capable of considerable dilation during action.

Ears:

Short, wide apart, alert, finely drawn, often noticeably in-pricked at the tips.

Head:

Wide, vaulted forehead (in most cases the parietal bones do not form a crest but remain open to the occipital crest). Frontal bone should blend into nasal bone in a pleasing slope. Very deep, prominent jawbones and great width between jawbones where they join at the throat. Head tapers to a fine, firm muzzle.

Neck:

Long supple neck with a finely modelled throatlatch.

Shoulders and Withers:

Long, sloping, well modelled, with good withers.

Body:

Characteristically slim with deep girth. Chest width in proportion to width of body. It is a fault to have “both legs out of the same hole”. Close coupled, with well defined hindquarters and good “saddle space”.

Quarters:

Long and sloping from hip to point of buttocks. Great length from stifle to hock.

Hocks:

Owing to their mountain origin, Caspians have more angled hocks than lowland breeds.

Limbs:

Characteristically slender with dense, flat bone and flat knees. Good slope to pasterns, neither upright nor over sloping.

Hoofs:

Both front and back are usually oval and neat, with immensely strong wall and sole, and very little frog. It must be emphasized, however, that this might vary with location and terrain and hoofs should be maintained in their natural shape to ensure correct hoof balance and soundness. They should never be artificially shaped.

Coat, Skin and Hair:

Skin thin, fine and supple, dark except under white markings. Coat silky and flat, often with iridescent sheen in summer. Thick winter coat. Mane and tail abundant but fine and silky. Mane usually lies flat (as in Thoroughbreds) but can grow to great lengths. Tail carried gaily in action. Limbs generally clean with little or no feathering at the fetlock.

Colours:

All colours, except piebald or skewbald (pinto). Greys will go through many shades of roan before fading to near white at maturity.

Height:

Varies with feeding, care and climate. Growth rate in the young is extremely rapid with the young Caspian making most of its height in the first 18 months, filling out with maturity. The average height is 11.2 hands high (hh)(1.17m) and ideally should not exceed 12.2 hh (1.27m).

Action / Performance:

Natural floating action at all gaits. Long low swinging trot with spectacular use of the shoulder. Smooth, rocking canter, rapid flat gallop. Naturally light and agile with exceptional jumping ability.

Temperament:

Highly intelligent and alert, but very kind and willing.

The Caspian Breed Type and Standard may not be reproduced unless it is done so in its entirety, free of omissions or amendments